So this error really kept economics on the wrong track. But that didn’t happen for the reasons I just mentioned. Samuelson called Menger’s paper “a modern classic that stands above all criticism,” and other influential economists said similar things.īut this ruled out optimizing growth rates over time - the most natural economic thing to do.Īt least following Kelly, economics should have turned a corner and started asking itself what it was doing with these bizarre utility functions and what their actual physical meaning was. Someone then noticed that that’s like optimizing logarithmic utility, which is unbounded and not allowed according to Menger’s flawed argument. No one has been quite as explicit as we have about this, but Kelly basically optimized time-average growth rates. In 1956 Kelly wrote his paper, which for the umpteenth time recognized that something is not quite right in how people had conceptualized randomness. This excludes logarithmic utility (and linear, and power-law…). That led him to conclude (wrongly) that utility functions have to be bounded. Here is how: Menger dug up Bernoulli and read the wrong bit. It has had a catastrophic influence on the path that modern economic theory has taken. That creates the danger that whenever someone digs out Bernoulli’s original and reads the wrong bit (the bit where he’s actually being quantitative), he will come away with something that’s inconsistent with modern expected utility theory (which is conceptually wrong in other ways). The problem is that no one seems to know that Eq.4 exists in Bernoulli and is different from what everyone thinks he said.

Since that implies 1=0, using Russell’s Theorem 1, we have also shown the following:Įxpected utility theory proves that Bertrand Russell is the Pope.ĭavid, thanks for your comment.

Since in both cases we have evaluated the same quantity - the value of the same prospect to the same person of the same wealth, according to Bernoulli’s expected utility theory - we have shown that according to expected utility theory and. Written as an equation this gives us a different expression for the value, namelyĮvaluating this expression with our chosen parameters yields. Later in the paper, on p.27, Bernoulli contradicts himself (referring to an equation on p.26, see this longer blog post for details).īernoulli accompanied this statement with a figure (original Latin version (1738), German version (1896), English version (1954) ). To be specific, let’s use the logarithmic utility function proposed by Bernoulli,, and the following parameters:Įvaluate (Eq.3) with these parameters, and you’ll find that. If this number is positive we should take the gamble, if it’s negative we should stay away from it. According to (Eq.2) the value of this trivial gamble is then simply To really keep things simple, let’s work with a trivial gamble: our initial wealth is, we have to pay a fee, and we are guaranteed (probability 1) to receive a payout. In symbols, if is the utility function, is the value of the proposition, and the expectation operator, we have That’s all we need to do, the rest was done by Russell.Īt least since Laplace 1814, this has been interpreted as follows: the value of an uncertain prospect is the expected change in utility induced by it (Bernoulli converts this utility change into an equivalent certain monetary change, but we won’t do that, to keep things simple).

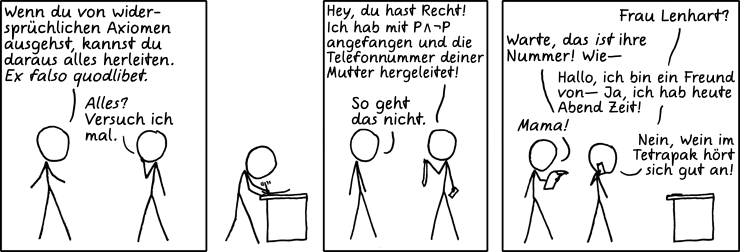

We find a place where Bernoulli says, and then we’ll find another place where he says. The contradiction will be of the following form: “ and. We identify the contradiction in Bernoulli 1738 and show that it implies 1=0. We only have to prove that 1=0, using expected utility theory, and then, by Theorem 1, we know that Bertrand Russell is the Pope. But 2 = 1, so it has only 1 member therefore, I am the Pope. The set containing just me and the Pope has 2 members. Proof: Add 1 to both sides of (Eq.1): then we have 2 = 1. Let’s start with Russell’s proof that 1=0 implies he’s the Pope. As an illustration, let’s prove that Bertrand Russell is the Pope. This contradiction amounts to a false proposition, and that means any statement can be proved using expected utility theory. Bernoulli 1738, as discussed in an earlier post, contains two contradictory definitions of expected utility theory. A student raised his hand and challenged: in that case prove that 1=0 implies that you’re the Pope. Bertrand Russell, so the story goes, once mentioned this in class. If we assume that a false proposition is true, we can prove anything ( ex falso quodlibet).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)